D. staphisagria

| Growing

History:An

illustrated revision of an article written by David

Bassett for "Delphiniums 98", the YearBook of

the Delphinium Society |

A quick look at books about delphiniums shows

that many begin by referring to the recognition by the ancient

Greeks of the dolphin-like appearance of the unopened flower. The

next sentence then introduces Delphinium staphisagria and

mentions the almost magical properties of its poisonous seeds as

herbal medicine or pesticide. To most gardeners, however, this

plant remains just part of Greek mythology, rather than a living

representative of the flora of Greece. D. staphisagria thus

represents a challenge but in 1997 I succeeded in growing it to

flower.

Seed of D. staphisagria, which is a biennial, is

seldom available and my first attempts to grow it some years ago

were with seed Shirley obtained via seed exchanges between

Botanical Gardens and Universities. This time we bought seed

listed by the Archibalds, which had been collected from plants

growing among open scrub at 750m at Anapoli, Crete. The plant

name refers to the resemblance of the leaves to a grape or 'wild

raisin' but you could be forgiven for thinking it was the large

seeds that looked like raisins. They should certainly not be kept

in the cupboard with your dried fruit! The average size for the long

axis of 32 seeds was 6.2 mm and the average width across the

seeds was 5.2 mm. The seeds are angular with flat facets and a

rough, ridged dark brown skin.

Seed of D. staphisagria, which is a biennial, is

seldom available and my first attempts to grow it some years ago

were with seed Shirley obtained via seed exchanges between

Botanical Gardens and Universities. This time we bought seed

listed by the Archibalds, which had been collected from plants

growing among open scrub at 750m at Anapoli, Crete. The plant

name refers to the resemblance of the leaves to a grape or 'wild

raisin' but you could be forgiven for thinking it was the large

seeds that looked like raisins. They should certainly not be kept

in the cupboard with your dried fruit! The average size for the long

axis of 32 seeds was 6.2 mm and the average width across the

seeds was 5.2 mm. The seeds are angular with flat facets and a

rough, ridged dark brown skin.

The first step is to germinate the seeds, so we

tried several methods. I chitted 10 seeds on wet paper towel in a

box on a propagator at 22ºC. Shirley put her 10 seeds on wet

paper towel in a box that went into the fridge for a cold, wet

soak before keeping them at room temperature. In view of the hard

skins, I chipped 5 seeds as is often done for seeds of sweet peas

. After 16 days, there was great joy because one chipped seed had

put out a root. That was in February, but it was to be the only

germination until after I abandoned chitting and sowed the

remaining 9 seeds in the garden in early May. Four weeks later,

after some warm weather and occasional rain, three more seedlings

germinated and grew to plants that flowered in September.

Obviously, we are unable to provide a more

reliable recipe for germination of this species than commiting

the seeds to the care of mother nature.

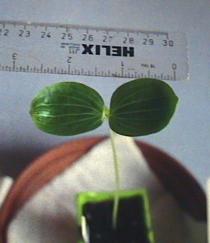

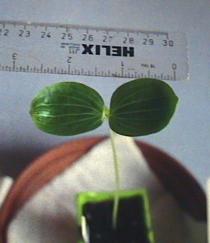

The first germinated seed was sown in a small

pot of compost and quickly grew to 'world record' size for a

delphinium seedling, measuring 7cm (2.75in) across the

cotyledons. Growth from then on was uneventful, producing a

rather lush plant with a hairy stem, fairly similar to the

closely related biennial species D. requienii but without

the glossy surface to the leaves. Unlike D. requienii, the

foliage has no offensive odour, even if crushed. The flower

spike emerged by early July and the flowers opened after another

two weeks.

The bloom is a very

loosely-packed, tapered raceme with quite small individual

florets (40 mm diam.) held on stiff pedicels (90 mm long at base

of bloom) with a bract and a pair of bracteoles right at the

base. The bloom was 50cm long with 27 florets and the blooms of

the later plants were of similar size, giving plants with a total

height of 1.2m (4 ft). A notable feature of the floret is that the spur is

little more than a nob on the back and is far shorter than for

the smaller flowers of D. requieni.

The bloom is a very

loosely-packed, tapered raceme with quite small individual

florets (40 mm diam.) held on stiff pedicels (90 mm long at base

of bloom) with a bract and a pair of bracteoles right at the

base. The bloom was 50cm long with 27 florets and the blooms of

the later plants were of similar size, giving plants with a total

height of 1.2m (4 ft). A notable feature of the floret is that the spur is

little more than a nob on the back and is far shorter than for

the smaller flowers of D. requieni.

Flower development is interesting in that

sepals are greenish yellow on opening. Colour then develops quite

slowly, starting from a deep inky-blue edging, moving inwards

along the veins and spreading out until the sepals are completely

blue.

The petals forming the eye also become coloured

and the prominent anthers are purplish brown. The flowers of the

plants that grew outdoors in strong sunshine became quite purple,

so it is easy to see how one can be confused by descriptions of

the colour of this species given in Flora.

|

|

|

The flowers produced plentiful supplies of

pollen, so I tried cross-pollinating with D. requienii, using

emasculated florets of the latter as the seed parent. These set

seed, so the next step will be to find out what sort of plants

they produce. (Not done due

to house move) The flowers of D.

staphisagria also set seed quite readily but, at that stage,

the first plant suddenly developed a nasty fungal infection at

the base of the stem. It seemed likely to die before the seed

could mature so, in desperation, I cut off the bloom and kept it

in water containing Chrysal cut flower food for the next two

months. This worked and seeds developed even on some of the

laterals. Ripening of the seeds seems to be very slow under UK

conditions and those set on the plants in the ground were too

late to ripen at all. It

is interesting that even under bad conditions, seeds have their

characteristically large size. The

thick-skinned inflated seed pods contain just two or three seeds.

The seed yield from

this species is consequently much smaller than from D.

requienii, which produces 35+ smaller seeds

per floret. The plants die once the seed has ripened.

I ended with four times more seeds than I

started with. At this rate of multiplication I would never have

sufficient seed to offer D. staphisagria in the seed list

of the Delphinium Society. I have no regrets about this, as my

impression is that it has less to offer as a plant for garden

decoration than D. requienii.

I am

now satisfied that I have seen the full life cycle of this

fascinating plant. However, it must produce more seed in the

wild, or the ancient Greeks would not have had enough to make

insecticide powder. To check this, I would of course need a trip

to the Greek holiday islands to obtain personal experience of the

environment where it grows!

Notes on the

availability of seed of D. staphisagria

Seed said to be of this species is sometimes offered by

Commercial seed suppliers and Specialist Societies. This winter,

2000/2001, we ordered seeds from The Hardy Plant Society and

Chiltern Seeds. In both cases the seed is too small to be D.

staphisagria. We have checked with Prof. Cèsar Blanché, an

authority on delphiniums of the Mediterranean area, that seed

size is indeed a clear distinguishing feature between this

species and the rather similar D. requienii.

Seed said to be of this species is sometimes offered by

Commercial seed suppliers and Specialist Societies. This winter,

2000/2001, we ordered seeds from The Hardy Plant Society and

Chiltern Seeds. In both cases the seed is too small to be D.

staphisagria. We have checked with Prof. Cèsar Blanché, an

authority on delphiniums of the Mediterranean area, that seed

size is indeed a clear distinguishing feature between this

species and the rather similar D. requienii.

In our experience, seed of D. requienii

is smaller and of a recognisably different shape. Plants of this

species are extremely prolific seed producers and the seed

germinates very easily.

Seed of D. staphisagria, which is a biennial, is

seldom available and my first attempts to grow it some years ago

were with seed Shirley obtained via seed exchanges between

Botanical Gardens and Universities. This time we bought seed

listed by the Archibalds, which had been collected from plants

growing among open scrub at 750m at Anapoli, Crete. The plant

name refers to the resemblance of the leaves to a grape or 'wild

raisin' but you could be forgiven for thinking it was the large

seeds that looked like raisins. They should certainly not be kept

in the cupboard with your dried fruit! The average size for the long

axis of 32 seeds was 6.2 mm and the average width across the

seeds was 5.2 mm. The seeds are angular with flat facets and a

rough, ridged dark brown skin.

Seed of D. staphisagria, which is a biennial, is

seldom available and my first attempts to grow it some years ago

were with seed Shirley obtained via seed exchanges between

Botanical Gardens and Universities. This time we bought seed

listed by the Archibalds, which had been collected from plants

growing among open scrub at 750m at Anapoli, Crete. The plant

name refers to the resemblance of the leaves to a grape or 'wild

raisin' but you could be forgiven for thinking it was the large

seeds that looked like raisins. They should certainly not be kept

in the cupboard with your dried fruit! The average size for the long

axis of 32 seeds was 6.2 mm and the average width across the

seeds was 5.2 mm. The seeds are angular with flat facets and a

rough, ridged dark brown skin.

The bloom is a very

loosely-packed, tapered raceme with quite small individual

florets (40 mm diam.) held on stiff pedicels (90 mm long at base

of bloom) with a bract and a pair of bracteoles right at the

base. The bloom was 50cm long with 27 florets and the blooms of

the later plants were of similar size, giving plants with a total

height of 1.2m (4 ft). A notable feature of the floret is that the spur is

little more than a nob on the back and is far shorter than for

the smaller flowers of D. requieni.

The bloom is a very

loosely-packed, tapered raceme with quite small individual

florets (40 mm diam.) held on stiff pedicels (90 mm long at base

of bloom) with a bract and a pair of bracteoles right at the

base. The bloom was 50cm long with 27 florets and the blooms of

the later plants were of similar size, giving plants with a total

height of 1.2m (4 ft). A notable feature of the floret is that the spur is

little more than a nob on the back and is far shorter than for

the smaller flowers of D. requieni.

Seed said to be of this species is sometimes offered by

Commercial seed suppliers and Specialist Societies. This winter,

2000/2001, we ordered seeds from The Hardy Plant Society and

Chiltern Seeds. In both cases the seed is too small to be D.

staphisagria. We have checked with Prof. Cèsar Blanché, an

authority on delphiniums of the Mediterranean area, that seed

size is indeed a clear distinguishing feature between this

species and the rather similar D. requienii.

Seed said to be of this species is sometimes offered by

Commercial seed suppliers and Specialist Societies. This winter,

2000/2001, we ordered seeds from The Hardy Plant Society and

Chiltern Seeds. In both cases the seed is too small to be D.

staphisagria. We have checked with Prof. Cèsar Blanché, an

authority on delphiniums of the Mediterranean area, that seed

size is indeed a clear distinguishing feature between this

species and the rather similar D. requienii.